skip to main |

skip to sidebar

... FOR "TWENTY YEARS LATER: 'JURASSIC PARK' (AN APPRECIATION - OF SORTS)"

Jurassic Park gets a fancy new

upgrade on Blu-ray this month (in 3D!) after raking in an additional $42 million

in U.S. theaters (including one week in IMAX) since April 5th. I haven't been

too enthusiastic about these post-converted 3D re- releases so far (read here

for evidence on that), but I have to admit seeing Steven Spielberg's 1993

dinosaur epic again on the big screen might have its perks. (That sublime

raptors-in-the-kitchen climax, in full-on jump-at-your-face three-dimensional

glory? Yes, please!) I've resisted the urge to buy a ticket, though, since I

happened to catch the movie twice on TV during the last week (once on DVD, and

the other during its regular rotation on Starz), and I realized that my appreciation

for it hasn't dwindled a bit since my initial viewing 20 years ago.

Even on the small screen, to witness Jurassic Park again is to be reminded of two things: one, that it

helped change the face of CG special effects work as we know it, and two, it's

a prime example of Spielberg's unparalleled genius as a virtuoso action director. No

one can deny that the dinosaurs are the stars of the show - a glorious mix of

computer-generated images, animatronics, and sound design. But without

Spielberg's sly signature wit Jurassic

Park might have turned out to be just another mindless monster movie.

Purists complain that it soft-pedals Michael Crichton's original

novel - takes some of its loftier ideas (chaos theory, fractals, the dangers

of technology inherent in nature) and makes mincemeat out of them instead. I've

always felt that the characterizations suffered most, especially when compared

to Spielberg's earlier, more character-based efforts. Take Jaws, for instance, about the hunt for a

man-eating killer shark - except it's not about the shark. It's about the three

men on that boat: the small town police chief, recently uprooted from New York to

New England, with a deathly fear of the water; the hotshot ichthyologist with

thousands of dollars at his disposal and something to prove; and finally, the salty old

shark hunter with a deep-seated hatred of his prey. Jurassic Park, on the other hand, is about a sarcastic

mathematician, a paleobotanist, and her paleontologist boyfriend who doesn't

like kids - on the run from genetically-cloned mutant

dinosaurs.

The movie is also positively overflowing with continuity errors and

dangling plot threads - none of which, by the way, do a thing to sour Jurassic Park's two-decade reputation as

a nonstop visceral thrill ride. It's these

nagging continuity errors I wish to discuss today - and how, because of Spielberg's

sheer command of the medium, they tend to have zero effect on the movie itself.

A "continuity error," for those not in the know, is any noticeable jump between shots in a given film. A character will suddenly shift

positions from one angle to the next, say, or the amount of liquid in a glass

will change levels throughout a selected scene. This is often caused by gaps in

the filmmaking process, including complex camera changes or shooting entire

scenes out of sequence. (David Bordwell speaks more astutely about continuity errors

here.) Some of these are minor, as in these subsequent shots from 37:22 and 37:23 of the Jurassic Park DVD (2000 edition). Note the position of John Hammond's hands from shot to shot:

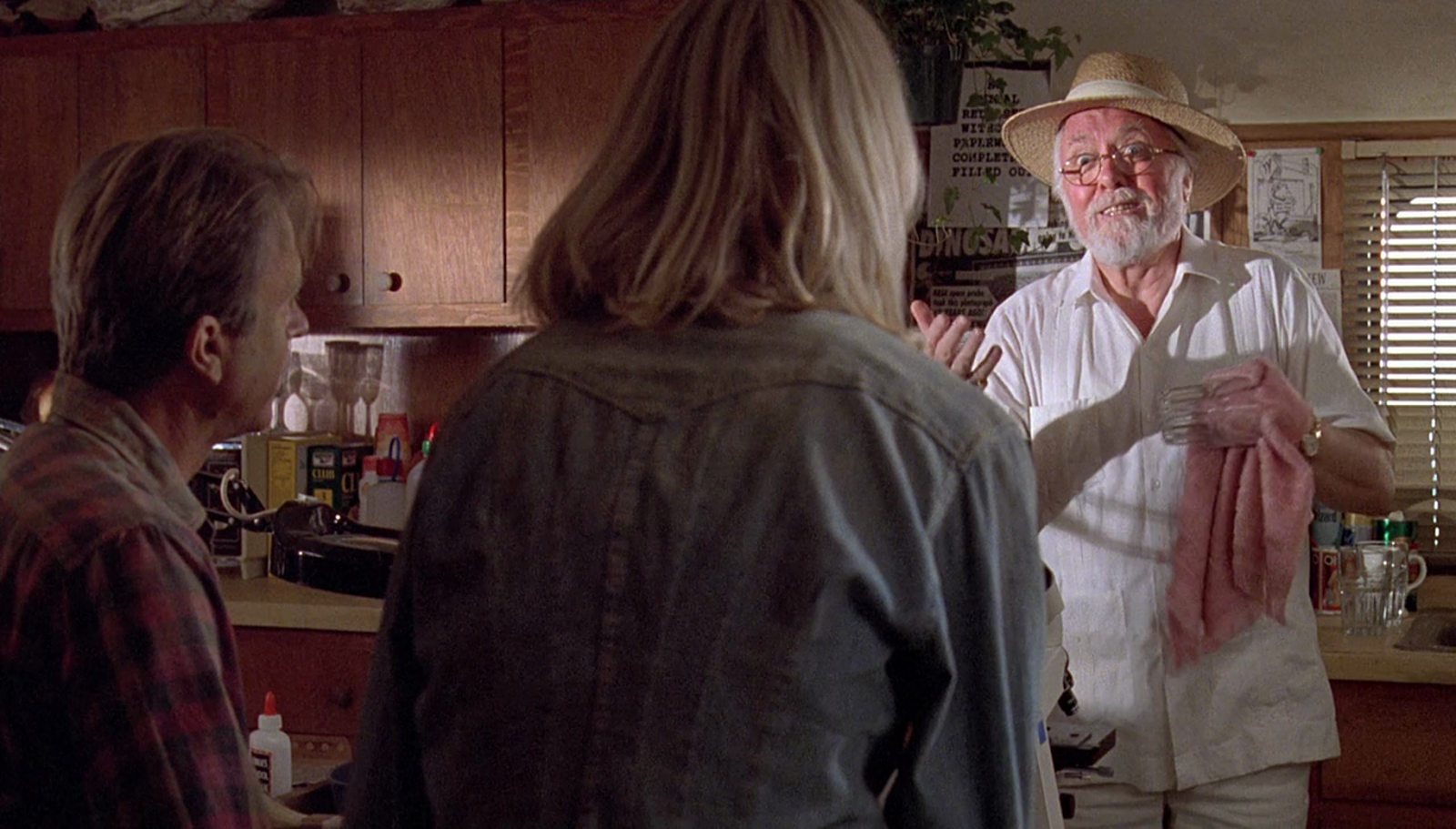

This is common, since actors' performances are rarely the same take after take. Other shots, however, are not so forgivable. Consider this scene, earlier in the movie, when Hammond visits Dr. Sattler and Dr. Grant to extend them a formal invitation to the park:

Did you catch it? That's right: In shot #1 (at 12:32 into the movie), the eccentric old billionaire cleans a drinking glass with a small white washrag in his left hand. But then, in shot #2 (at 12:33), the washrag magically switches to a larger pink towel! That's quite the trick, no?

Or consider this scene inside the Jurassic Park hatchery/nursery, where the characters are granted a front-row seat to a live dinosaur birth. At 30:07, a large robotic arm is clearly seen holding the velociraptor egg in its place. Then, when the camera switches to a different POV at 30:08, the robot is nowhere to be found!

Later, continuity errors will seep into the set pieces as well. And again, while the action is going you probably won't care. First up, the tyrannosaur attack - easily the most iconic scene in the movie. The gaffe comes at the end, after the T-Rex has threatened the children (knocking over their tour car in the process) and eaten Gennaro sitting on the toilet. The rex then returns to the overturned jeep, forcing Dr. Grant and Lex onto the concrete barrier behind them and ultimately down the other side:

But wait: Where did that sixty-foot drop come from? Let's backtrack a bit and take a look at the following shot, of the tyrannosaur stepping through the (un)electrified fence in between the two vehicles. Clearly, it's walking on solid ground as it exits the paddock:

Moments later, though, when the characters wind up in the exact same spot, the ground behind them has miraculously disappeared! Was the tyrannosaur walking on air?

You could argue, I suppose, that the rex simply nudges the jeep down a different part of the fence. Yet have a look at this shot (of Malcolm on the run), and you'll see that only one section is missing the electrical wire:

JP's second most spectacular set piece (in a film full of spectacular set pieces) is the climactic raptors-in-the-kitchen scene, in which two of Earth's deadliest creatures are outwitted by a pair of plucky kids. Spielberg stages the action with such verve and hair-trigger suspense that the scene's biggest flaw (it comes at the beginning) makes practically no impression at all.

Spielberg prefaces the scene with a couple of ingenious shots. First, one of Lex holding a spoon of quivering Jell-O, her eyes wide with fear:

Next, what she sees: the silhouette of a velociraptor, emerging from behind a slightly less intimidating painting of a similar animal. Timmy sees it too, and turns toward the camera with an audible gasp:

Note Timmy's comically frizzy hair, from his run-in with a (re)electrified fence just a few short moments ago. Which makes it all the more confusing when, the next time we see him (in the kitchen), his hair is neatly combed - damp, even!

No doubt Spielberg and his collaborators made the change on purpose (because nothing drains the fun out of a sequence more than the sight of a white kid with an afro). Besides, who cares what the kid looks like when there's so much of this going on:

Finally, the T-Rex rescue at the end of the film. Even today, there's some confusion over the rex's sudden appearance in the Visitor's Center. But that's a mystery easily solved. Here, the second raptor to corner the characters (or third, including the one trapped in the freezer) enters through the white construction tarp at the rear of the room:

The tyrannosaur, presumably, follows the raptor inside, ripping the canvas to shreds as it does so:

I think the bigger mystery here is the magically

appearing/disappearing raptor trick. It's virtually undetectable when

watching the movie at normal speed. Play it back one frame at a time, though,

and you can see that the velociraptor disappears for a single frame as

it's picked up in the tyrannosaur's jaws. Now you see it:

Now you don't:

An honest mistake on the filmmakers' part? Or a curious insight into the mindset of computer animators looking to cut a few corners? Either way, Spielberg keeps the action coming so fast, and his crowd-pleasing

instincts are so incredibly, unequivocally right, that flubs like these are hardly

worth the attention I've given them. (It may also never occur to people

that this "T-Rex To The Rescue" moment is

basically a narrative cheat. But that's a subject for a separate post.) Nitpicking or simple attention to detail, continuity errors are a natural part of the cinematic

language. So natural, in seems, that not even the world's most prolific directors can avoid making them.

(Many thanks to MovieMistakes.com for additional research and help.)

No comments:

Post a Comment